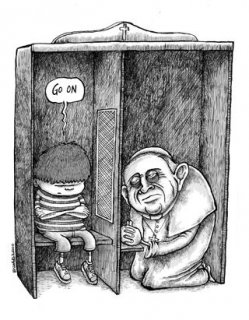

After Archbishop Robert Zollitsch's recent papal audience, he

spoke of Pope Benedict XVI's "great shock" and "profound

agitation" over the many cases of abuse coming to light.

Zollitsch, archbishop of Freiburg, Germany, and the chairman of

the German Bishops' Conference, asked pardon of the victims and

spoke again about measures that have already been taken or will

soon be taken. But neither he nor the pope addressed the real

question that can no longer be put aside.

After Archbishop Robert Zollitsch's recent papal audience, he

spoke of Pope Benedict XVI's "great shock" and "profound

agitation" over the many cases of abuse coming to light.

Zollitsch, archbishop of Freiburg, Germany, and the chairman of

the German Bishops' Conference, asked pardon of the victims and

spoke again about measures that have already been taken or will

soon be taken. But neither he nor the pope addressed the real

question that can no longer be put aside.

According to the German polling agency Enmid, only 10 percent of those interviewed in Germany believe the church is doing enough in dealing with this scandal, and 86 percent say the church's leadership shows insufficient willingness to come to grips with the sex abuse problem. The bishops' denial that there is any connection between mandatory celibacy for priests and the abuse problem only confirms these criticisms.

This recent series of events raises four key questions.

The first of these questions is why the pope continues to assert that what he calls "holy" celibacy is a "precious gift," thus ignoring the biblical teaching that explicitly permits and even encourages marriage for all office holders in the church?

Celibacy is not "holy"; it is not even "fortunate." It is "unfortunate," for it excludes many perfectly good candidates from the priesthood and forces numerous priests out of office, simply because they want to marry. The rule of celibacy is not a truth of faith, but a church law going back to the 11th century; it should have been abolished in the 16th century, when it was trenchantly criticized by the Reformers.

Honesty demands that the pope, at the very least, promise to rethink this rule - something the vast majority of the clergy and laity have wanted for a long time. Both Alois Glück, the president of the Central Committee of the German Catholics, and Hans-Jochen Jaschke, auxiliary bishop of Hamburg, have called for a less uptight attitude toward sexuality and for the co-existence of celibate and married priests in the church.

The second and related question is whether, as Archbishop Zollitsch insists, "all the experts" agree that the abuse of minors by clergymen and the celibacy rule have nothing to do with each other. How can he claim to know the opinions of "all the experts?" In fact, there are numerous psychotherapists and psychoanalysts who see a very direct connection. The celibacy rule obliges priests to abstain from all forms of sexual activity, though their sexual impulses remain virulent, and thus the danger exists that these impulses shift into a taboo zone and are compensated for in abnormal ways.

Honesty demands that we take the correlation between abuse and celibacy seriously. The American psychotherapist Richard Sipe has clearly demonstrated, on the basis of a 25-year study published in 2004 - under the title Knowledge of Sexual Activity and Abuse Within the Clerical System of the Roman Catholic Church - that the celibate way of life can indeed reinforce pedophile tendencies, especially when the socialization leading to it (adolescence and young adulthood spent in minor and major seminary cut off from the normal experiences of their peer groups) is taken into account. In his study, Sipe found retarded psycho-sexual development occurring more frequently in celibate clerics than in the average population. And, often, such deficits in psychological development and sexual tendencies only become evident after ordination.

The third question is, Shouldn't bishops at last admit their own share of blame? For decades, they have not only avoided the celibacy issue but also systematically covered up cases of abuse with the mantle of strictest secrecy, doing little more than re-assigning the perpetrators to new ministries. In a statement March 16, Bishop Ackermann of Trier, special delegate of the German Bishops' Conference for sexual abuse cases, publicly acknowledged the existence of such a cover-up, but characteristically he put the blame not on the church as an institution but rather on the individual perpetrators and the false considerations of their superiors. Protection of their priests and the reputation of the church were evidently more important to the bishops than protecting minors. Thus, there is an important difference between the individual cases of abuse surfacing in schools outside the Catholic Church and the systematic and correspondingly more frequent cases of abuse within the Catholic Church - where, now as before, an uptight sexual morality prevails - that finds its culmination in the law of celibacy.

Honesty demands that the chairman of the German Bishops' Conference should have clearly and definitively announced that, in the future, the hierarchy will cease to deal with criminal acts committed by those in the church by circumventing the state system of justice. Can it be that the hierarchy here in Germany will only wake up when it is confronted with demands for millions of dollars in reparation payments? In the United States, the Catholic Church had to pay some $1.3 billion alone in 2006; in Ireland, the government helped the religious orders set up a compensation fund with a ruinous sum of $2.8 billion. Such sums say much more about the dimensions of the problem than the pooh-poohing statistics about the small percentage of celibate clergy among the general population of abusers.

The final and biggest question asks, Is it not time for Pope Benedict XVI himself to acknowledge his share of responsibility, instead of whining about a campaign against him? No other person in the church has had to deal with so many cases of abuse crossing his desk. Here are some reminders:

In his eight years as a professor of theology in Regensburg, in close contact with his brother Georg, the Kapellmeister of the Regensburger Domspatzen choir, Ratzinger can hardly have been ignorant about what went on in the choir and its boarding school. This was much more than an occasional slap in the face; there are charges of serious physical violence and sexual abuse.

In his five years as archbishop of Munich, repeated cases of sexual abuse by at least one priest in his archdiocese occurred. His loyal vicar general, my classmate Gerhard Gruber, has taken full responsibility for the handling of this case, but that is hardly an excuse for the archbishop, who is ultimately responsible for the administration of his diocese.

In his 24 years as prefect of the congregation for the doctrine of the faith (his position before becoming pope), all cases of grave sexual offenses by clerics worldwide had to be reported, under strictest secrecy ("secretum pontificum"), to his office, which was exclusively responsible for dealing with them. Ratzinger himself, in a letter on "grave sexual crimes" addressed to all the bishops May 18, 2001, warned bishops, under threat of ecclesiastical punishment, to observe "papal secrecy" in such cases.

In his five years as pope, Benedict XVI has done nothing to change this practice with all its fateful consequences.

Honesty demands that Joseph Ratzinger himself, the man who for decades has been principally responsible for the worldwide cover-up, at last pronounce his own mea culpa. As Bishop Tebartz van Elst of Limburg, in a radio address March 14, put it: "Scandalous wrongs cannot be glossed over or tolerated, we need a change of attitude that makes room for the truth. Conversion and repentance begin when guilt is openly admitted, when contrition is expressed in deeds and manifested as such, when responsibility is taken, and the chance for a new beginning is seized upon."

- Father Hans Küng is a theologian and author of Does God Exist?: An Answer for Today and Infallible?: An Inquiry. He is director emeritus of the Institute for Ecumenical Theology at the Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen, Germany.This article is reprinted with the permission of the National Catholic Reporter, 115 E. Armour Blvd., Kansas City, MO 64111, www.ncronline.org.